The Finland Phenomenon - the best education system in the world?

I posted yesterday about the urgent need to change education paradigms.

As such it feels fitting to final re-post this post from Gloria’s blog here:

Have you noticed there’s a lot of hullabaloo about Finland’s education system lately? I’ve been paying attention to what the Finns have been doing for a couple years now, but it is only after reading an essay by Sam Abrams I’ve thought to pay attention to Finland’s neighbour Norway.

Norway and Finland have some similarities. They are neighbouring countries that each take up about 350 000 square kilometres with populations around 5 million and about 10 percent foreign born in Norway and 4 percent in Finland. A notable difference, however, is that Norway has a significantly higher Gross Domestic Product.

Norway has oil. Finland has trees. Since the 1970s, Norway has focused intensely on developing their oil and gas resources which have risen to 45% of their total exports and 20% of their GDP. These efforts have provided Norway with bragging rights over being the fifth largest oil exporter and third largest gas exporter in the world.

Meanwhile, Finland in 1971 realised that their natural resources, largely timber, weren’t going to cut it. They needed to modernize their economy and to do it they were going to have to improve their schools. In other words, they were going to have to focus intensely on developing their children’s brains.

To do this, Finland focused on reducing class size, improving formative assessment practices, increasing teacher pay & notoriety, and requiring all teachers to complete a master’s program. Finnish teachers use a relatively concise national curriculum to guide them in creating curriculum and assessment at the local level, and very little time, effort and resources are wasted with standardised testing; in fact, the only time a Finnish student would ever be required to write a standardized exam is if a high school senior planned on attending university (National Matriculation Examination). Finland has worked worked meticulously to ensure equity and opportunity thus reducing the number of Finnish children who live in poverty to 1 in 25.

Today, Finland’s education system is considered to be one of the best in the world.

Conversely, despite Norway’s similar demographics, their education reforms have followed a very different path than Finland’s:

- Their class sizes tend to be larger

- They struggle to find enough qualified teachers

- Rather than focusing on better trained teachers, Norway has thrown millions of dollars at a teacher preparation program similar to Teach for America called Teach First Norway where teachers get mere weeks of training.

- They implemented a national standardized testing system of accountability

- They have placed more time, effort and resources on summative assessment such as tests and grades.

- Based on PISA scores, Norway’s education system falls somewhere around mediocre.

So why is comparing and contrasting Finland and Norway important?

Upon hearing about the progress Finland has had with their education system, many policy-makers in other countries may be inclined to point towards the Finns smaller, more homogenous population as the primary reason for their successes in the classroom. That Norway and Finland can share such similarities in population and yet differ with their education systems may be enough proof that policy choices, rather than demographics, can play a potentially larger role in a nation’s educational success.

In Alberta, Canada, we have dedicated a considerable amount of time, effort and resources on becoming the world’s second largest exporter and fourth largest producer of natural gas while simultaneously helping Canada become the seventh largest producer of oil, just three spots ahead of Norway. While debating whether this is something Alberta or Norway should be proud of or not may make for an interesting discussion, such a dialogue is not the purpose of this post.

Let us acknowledge that the world is changing and so must our education system in order to prepare our children for a future we can not predict.

This is not up for debate.

Regions like Norway and Alberta run the risk of being blinded by what some have coined a “resource curse” or a paradox of plenty. A dependency on oil and gas can leave us grossly susceptible to excessive revenue volatility — things are glorious in the booms but down-right scary in the busts. It’s not unheard of to hear during these busts calls to balance the budget on the back of cutting spending on education, which ends up being the equivalent to a farmer selling the top-soil to pay the bills.

While regions like Alberta and Norway can afford to pay less time, effort and resources on their education systems, Finland’s lack of resources has forced them to invest “laser-like” attention on nurturing theirs. The good news is that if Finland can do this with less, the abundance of wealth in regions like Norway and Alberta can be used to do the same.

So if Finland’s successes in the classroom are less about their inherent Finnish characteristics and more about their policies, then it might be advantageous to identify how the Finnish differ from conventional education reforms.

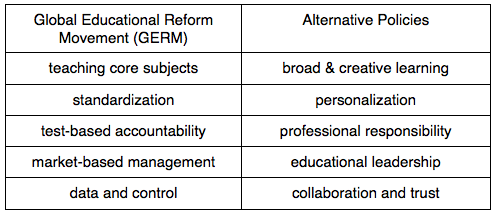

Pasi Sahlberg is a leading educator from Finland and former senior adviser in Finland’s Ministry of Education who writes and speaks about what the world can learn from Finland. The chart below contrasts what Sahlberg coins as The Global Education Reform Movement (GERM) with alternative policies that Finland has successfully enrolled:

In his post On a Road to nowhere, Sahlberg explains:

English education policies rely on more choice, tougher competition, intensified standardised testing and stronger school accountability. These are the key elements of the policies that were dominant in the United States, New Zealand, Japan and parts of Canada and Australia a decade or so ago. Available PISA data reveals the impact of these education policies on students’ learning between 2000 and 2009. The overall learning trend in all these countries is consistently declining. That is a road to nowhere. Many governments are taking note of the 2009 PISA results, but they are rather selective in reporting of the education systems that are doing well in PISA. Finland has been one of the few consistently high performing systems in PISA’s 10-year history. Significantly, Finland has not employed any of the market-based educational reform ideas in the ways that they have been incorporated into the education policies of many other nations, including the United States and England.

Finland’s successful pursuit of policies driven by diversity, trust, respect, professionalism, equity, responsibility and collaboration refute every aspect of reforms that focus on choice, competition, accountability and testing that are being expanded in countries around the world.

In short, it’s time to put ideology aside and focus intensely on the paradoxes of the Finland phenomenon.